Touring with Death and Danger: Exploring the World through Dark and Morbid Tourism

‘Where do they keep them now?’

It was common enough to get absurd, borderline offensive questions in my line of work as a tour guide in Berlin. But this question asked by a young South Korean woman to one of my colleagues would go down in Berlin tour guide history. Over a decade later, it still comes up when any of us former guides get together and reminisce about the complexities, joys, and difficulties of educating hoards of holidaying tourists about the horrors of Germany’s 20th century activities.

‘Pardon?’

This was the response given by my lovely Kiwi colleague, to whom the question was directed. It was a common ploy we guides used when asked something so ludicrous, something that caught you so off guard, you had to mentally buy yourself time to think of a diplomatic, professional response. This response was also used with specific tourists to allow the question-asker a chance to think about the remarkably stupid thing they said — I know this sounds harsh, but you ask anyone who has worked with the general public and they will know that I am being delicate and could be far meaner — and retract it with their pride somewhat intact once their brain was given a chance to catch up with their mouth.

Most people jump on that opportunity and fucking cling to it, while internally chastising themselves for asking such a ridiculous thing, out loud, directly into the face of another human being. We’ve all done it. As a tour guide, I got used to seeing the looks of embarrassment and shame as the question-asker silently berated themselves in their own head and fought the desire to die. Not our South Korean friend. She doubled down.

‘Where do they keep them now?’

My Kiwi colleague had met her match. It was a Saturday morning in summer, our busiest day of the week during high season. Our meeting point was the Brandenburg Gate, one of the busiest spots in Europe. She was trying to deal with colleagues speaking in German, Spanish, and English and tourists speaking in dozens of other languages. She was the lead guide for a tour that went to a memorial outside of the city, so was organising not just ticket sales but keeping an eye on the departure time of the train. Our South Korean friend had a ticket for this tour. She had found her guide, showed her ticket, and then proceeded to absolutely mind-fuck my colleague by asking:

‘Where do they keep them now?’

That is how both this tourist and my colleague started a day-long excursion together to Sachsenhausen, the former Nazi concentration camp just outside of Berlin.

‘Keep who?’

My colleague later told the rest of us that when she asked this she was crossing every finger and toe, praying to any god or deity that has existed in the past, currently existed, or is likely to exist in the minds of generations of humans not yet born, that she had misunderstood the question that was being presented.

‘The Jews.’

Nope. My colleague had not misunderstood. This tourist thought that she would be visiting a still functioning Nazi forced labour camp complete with real prisoners. My colleague was now in every tour guide’s worst nightmare — having to maintain a poised air of professionalism when faced with a question of remarkable sensitivity. For anyone who hasn’t had to do this, it’s the conversational equivalent of bomb disposal. Except in this case, the bomb doesn’t explode right away, the bomb follows you around for 3-8 hours, judging you, threatening to detonate at any moment, and making your day hell.

The rest of us guides found this situation highly amusing, for three main reasons:

The question’s absurdity makes it funny

We were so used to getting questions that ranged from the heartbreaking to the unhinged and had developed a dark sense of humour to cope — if you didn’t you cried yourself to sleep at night

We were thrilled that it wasn’t us that had to answer while remaining professional…this time; we knew our turn was always lurking nearby

My colleague handled it like a legend. However, the situation, although entertaining for anyone that isn’t my colleague or this particular tourist, emphasises in a single interaction the simultaneous need to learn about darker historical events through site visitation and to be aware of the problematic behaviour and rhetoric of some of the visitors to these sites.

As tourists, we find ourselves in this fucked up limbo, oscillating between properly educating ourselves to ensure we learn from past mistakes so we don’t repeat them and looking like we’re using the pain and suffering of others to fill days on a holiday. There are complexities that come with visiting historical sites of pain, suffering, death, and danger — partaking in what has come to be known as ‘morbid tourism’ or ‘dark tourism’.

There is a slight difference between ‘morbid tourism’ and ‘dark tourism’, although they are often used interchangeably, and I suspect that they will blur to mean the same thing in the near future. However, with nuanced topics such as these, I believe it is best to highlight the key aspects that differentiate them.

Morbid tourism is the practice of visiting places where death, usually mass or systemic murder, is at the centre. Places such as Auschwitz or the Killing Fields, where government regimes created, organised, and ran the operations that eradicated large numbers of civilians over a lengthy period of time, would be examples. Dark tourism, which is becoming the more widely used term, is a bit broader and describes the visitation to places of disaster, tragedy, death, or danger. Places like Chernobyl, the Suicide Forest, dangerous or forbidden border areas, and abandoned cities where visitation is illegal would fit under the umbrella of dark tourism. The reasons for partaking in either form of travel, and whether tourists should be able to travel in this manner, remains very much open to debate. Personally, I am an advocate of morbid travel for educational purposes; I have a slightly more negative view of dark tourism. The difference, for me, lies in the motivations behind why tourists partake in them.

Learning about the history of a place opens up a deeper appreciation of, not just that location but, the culture and people that live there. In doing so, we are quickly confronted by the darkness that comes with human existence and behaviour. Every country has a dark part of its past, sometimes lurking just beneath the surface but shamefully hidden away, and other times it’s purposefully put on display as a lesson so the worst parts of human history are never repeated.

As a former licensed tour guide at Sachsenhausen, a former Nazi concentration camp located just outside of Berlin and where my dear colleague and her South Korean tourist friend would spend the day together, I have seen my fair share, perhaps more than my fair share, of tourists interacting with the morbid side of tourism. It taught me a valuable lesson — people will always find ways to surprise you. Good or bad.

We humans seem to have a strange relationship with death and pain. When confronted with these, some tourists squirm, unable to look directly at certain photos, information placards, or artefacts, or, if they can look at them, they cannot do so for any length of time; others, despite the distressing nature of what they are seeing, simply cannot look away, either out of a morbid, duty-bound willpower to look the proof of the worst of human behaviour in the eye, or out of sheer curiosity and wonder at how such events could take place that would lead to the creation of the physical evidence in front of them.

I have witnessed family members of survivors smile in defiance; heard the chattiest tourists go silent, not saying a word for hours, undergoing complete and total personality bypasses; I have had emotionally mature discussions with once bravado-filled teenage boys who have been hit with the realisation that had they been born at a different time, they would be the statistic that they have read off a placard; I have witnessed men presenting themselves as hyper-masculine and too-tough-for-emotions break down in tears; I have heard tourists who, on the surface appeared to be the gentlest, friendliest people, say reprehensible slurs. I feel that I have experienced the full range of human emotion and reaction to the worst of human behaviour.

Over the years, I trained myself, as most tour guides do, to react accordingly and professionally to each of these situations. The only reaction that ever put me on edge, made me feel a prickly, heightened sense of discomfort, and was almost impossible to respond to, was indifference. I never understood, and never will understand, how anyone can be confronted with human suffering and not have some reaction — even if it is in the form of silly or, on the surface, ignorant questions because at least those open the door to genuine learning opportunities. What I found in those ‘ignorant’ questions, like “Where do they keep them now?’, is a desire to learn, but from someone who grew up in a different education system that didn’t teach the same battles, wars, or genocides that I learned about.

There has been a lot of dark, fucked up history, it makes sense that different countries teach different historical events with varying degrees of importance and significance. It’s not, necessarily, an undermining of those events, it’s simply that we don’t have the capacity to learn about everything in depth — our brains would fucking explode. What I loved about tourists, like our South Korean traveller, is that the majority of them, even if they lacked a bit of grace or decorum when doing so, still had a desire to educate themselves thoroughly. In more cases than not, by the end of their time in morbid places, they walked away with a deeper understanding and appreciation of what other human beings suffered through. They left having learned something valuable, even if they were initially drawn in by the morbidity.

Why we seem to have this weird fascination, bordering on obsession, with misfortune, hardship, and death, is a question I ask myself regularly and I’m not alone. It is one of the main questions underpinning dark tourism.

Maybe it reminds us that we’re lucky and puts our own good fortune into perspective. Maybe it’s because in many, what are often termed as ‘Western’, cultures, we’re becoming farther removed from death and the processes that surround it, and therefore fear it more and seek more answers. Maybe it’s because we get a thrill, a wee fanny-flutter even, from seeing pain and experiencing danger. Or maybe it’s because, as a species, we’re just a bit fucked up.

The reasons behind it or your opinion of morbid and dark tourism — whether you believe it is beneficial for deeper cultural and historical understanding of a place, a people, a history, or whether you think it is an abomination and simply an excuse to use engagement with the historical suffering of others to make yourself feel like a better, more righteous, or more adventurous and brave human being — doesn’t change the fact that it’s a popular part of travel. I doubt very much that it’s going to disappear. Personally, I would be concerned if it did.

I firmly believe in the importance of learning history properly, approaching it from a range of perspectives, and not shying away from deeper, more thorough research. If you’re learning about some of the worst parts of human history it’s going to cause discomfort, it’s going to be ugly. If it isn’t, then you’re not learning about historical fact, you’re being fed a sugar-coated version of events crafted very intentionally to make a certain group look better than their true behaviour would illustrate. If you find yourself with a comfortable, palatable version of a dark historical event, it’s time to seek out other sources of information.

But by using places of suffering, such as the Killing Fields in Cambodia, sites of nuclear disaster such as Chernobyl, and former concentration camps like Dachau and Auschwitz, for educational purposes, we run the risk of turning these places of pain and death into mere backdrops for social media posts and bucket-list tick offs; the behaviour of some tourists and the subsequent measures taken by institutions, destinations, and local governments highlight this. While the majority of tourists do behave respectfully, unfortunately there are those that don’t, and in my time as a guide at Sachsenhausen and various European memorials and museums, I noticed a steady decline, a degradation even, in visitors’ behaviours in recent years.

So, as conscientious travellers, how do we make sure that we are approaching these spaces of historical importance with respect, decency, and open-mindedness? And what will the cost be for these spaces in the future if we don’t?

There are consistent issues that cause problems in these sites of morbidity and darkness: photos, dress code, and behaviour. Let’s address each individually and break down what is appropriate, what isn’t, and how to ensure that you are being on your best behaviour when you visit spaces of historical, cultural, or religious significance — dark and morbid or otherwise.

Photos

For years, it was a core part of my job to instruct tourists on the rules of memorial sites and ensure that they understood and were in agreement with those rules. If they did not comply, there were consequences. These ranged from being asked to leave the tour without a refund to a call to the police leading to an arrest, fines, and possible jail time. It is serious.

Photography is a nightmare. I’m always empathetic, or try to be — some tourists test the limits of my empathy and patience — and I understand why people want to document their travels to these sites. But a certain standard of respect for the victims has to be maintained in these spaces, and people push those boundaries.

My general advice to all tourists is this:

Take photos of the space – but there is no need for you to be in those photos.

If you think this is unfair, I encourage you to take a moment to reflect on why you feel the urge or the need to be in that photo. The moment that you place yourself in that photo, you become the centre of attention — whether that is your intention or not. A person in a photograph will almost always pull focus, relegating the place to the role of backdrop, a mere set dressing. Now ask yourself, why do you feel the need to be the centre of attention or focus at sites where people have suffered and died?

Follow the rules for photography and videos (if there are any).

Now, take a deep breath and maybe have a wee sit down if you’re not already, because this next bit is going to sting for a few of you. Ready?You are not as special as you think you are and you are definitely not the exception to the rule.

If you find yourself asking, ‘But does that rule apply to me?’ — the answer is yes, yes it does. If you still don’t believe me and find yourself asking, ‘But surely if just one person (moi) does it, it can’t do any harm?’ – wrong; you are the 3,000th person to have had that exact same thought today. If you don’t care and are going to do what you want to do anyway, then you’re a wanker and deserve the consequences of your selfish actions — do us all, but especially yourself a favour, and just get over yourself. You might find that you actually start to learn something from these spaces you’ve chosen to visit.

Dress Code

This one is tricky. It can be a complex and delicate topic so we’re going to try to traverse it together carefully (but possibly with a bit of on-brand swearing and sarcasm). I will say, that dress code is actually one thing that the majority of tourists, at least in my professional and personal experience, have no problem adhering to as a mark of respect.

That being said, when certain tourists don’t want to adhere to a site’s dress code, they tend to get very vocal about it. Very fucking vocal. Think Influencers in the Wild meets the ultimate Karen. Things tend to escalate and become heated fairly quickly. So that you’re in no danger of becoming one of those influencer-Karen hybrids, here are two simple reasons why adhering to specific forms of dress are important and necessary in certain locations.

1. It’s a cultural or religious thing.

It might not match what you believe but just a gentle reminder that you are not in charge when you are a guest in someone else’s country or culture. You don’t get to call the shots.

My advice is this, do your research. Research the acceptable dress code before you travel to any destination. If you believe that adhering to a specific dress code is going to cause you grief or trauma, then perhaps that destination or site isn’t right for you. If it isn’t for you, that’s ok, there are other places where you will feel much more comfortable.

2. It’s a safety thing.

In many dark or morbid destinations, wearing certain things, such as amulets, religious emblems, protective gear, high-visibility clothing, can be a matter of life and death.

I know there will be people who read the first two examples and scoff because they don’t believe in that sort of thing, but remember, you’re visiting places with cultures, religions, beliefs, and superstitions that you might know nothing about. If you wearing a certain symbol of guardianship makes your guide — the person whose job it is to keep you safe and get you home in one piece — feel comfortable, safe, and confident, then wear the fucking amulet.

Funnily enough, in my experience it isn’t the amulets and spiritual protection that tourists tend to fight against wearing, it’s usually the very obvious fucking safety gear. Just put it on. You look fine. Your pictures for The Gram will turn out. You’ll survive. Unlike if you don’t wear the fucking helmet.

Behaviour

Here we go. The biggie. As mentioned before, people will never cease to surprise you, and I have seen some truly shocking tourist behaviour in my time. In my experience, I have found that adhering to five simple rules will help eradicate most poor behaviour in places that require a bit of social decorum.

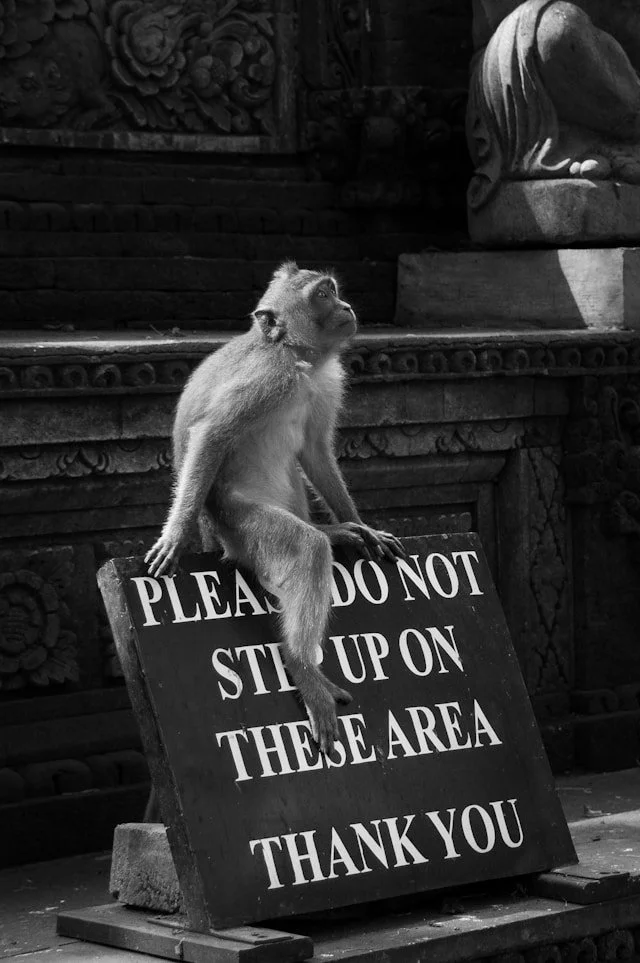

1. Stay in designated areas

2. Mind your manners

3. Think before you speak — and in some case, silence is your best friend

4. Follow guide instructions and signage

5. Be aware of other tourists

Ultimately, morbid tourism is going nowhere, and the reality is that we can expect it to increase in popularity as tourists and travellers become bored with more traditional destinations and activities. The debate surrounding the ethics and morality of dark tourism will continue. Supporters will argue that they are going to places that are less crowded, more educational, or culturally immersive and authentic while opponents will argue that those that partake in this variety of travel are self-absorbed gits with death fetishes or wishes.

The reality is that morbid tourism can create unique opportunities to learn about complex and nuanced historical events thoroughly, allowing tourists to engage with a history and a people in a manner that a textbook could never replicate. Dark tourism, although I, personally, am more critical of this version of tourism due to the locations people choose and the risk to safety and life that tends to come with it, can open doors to destinations and cultures that would otherwise go unexplored. Like most things in life, it is a complicated topic with no simple answer.

I’ll leave you with this: if you are going to make morbid or dark tourism part of your future itineraries, remember to travel with care, respect, and awareness. And, if making a trip to a former concentration camp, maybe try to refrain from asking, ‘Where do they keep them now?’. Although, a potential door to a new learning journey, I know your guide will be forever grateful if you don’t ask that.